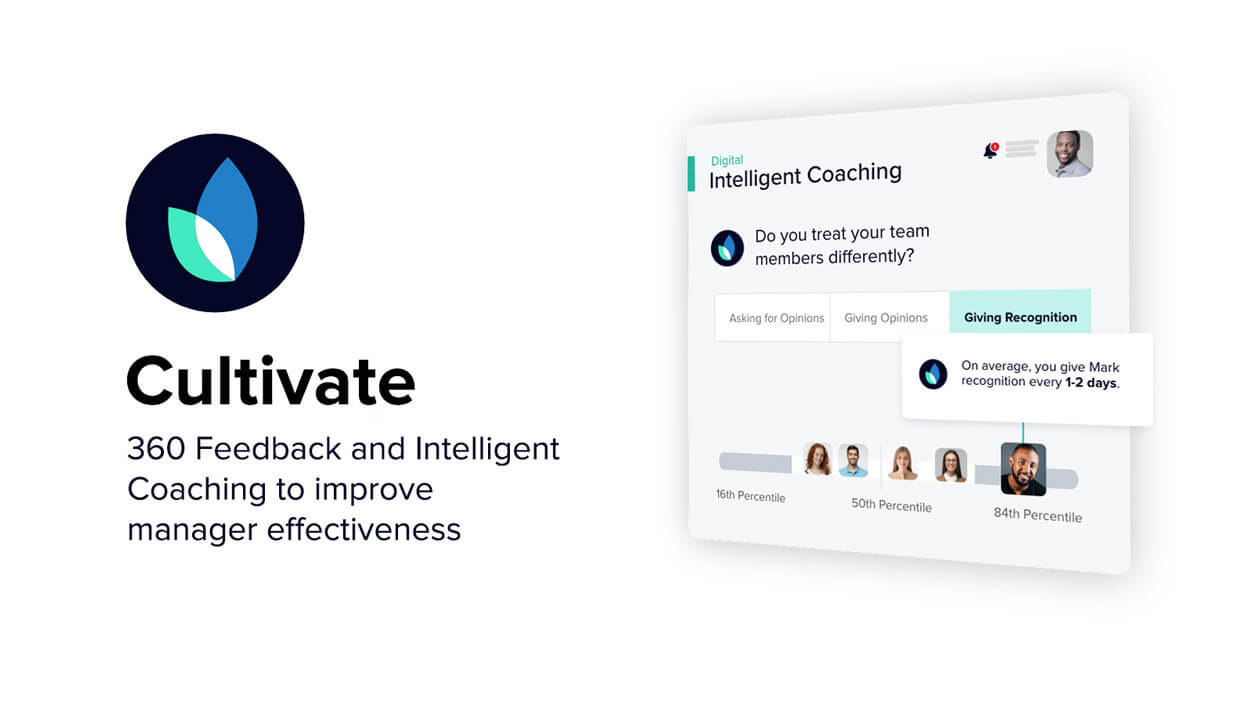

Cultivate

Transform managers into leaders.

Unleash leadership potential with Cultivate

In today’s hybrid and distributed workplace, where interactions occur through digital platforms like Slack and Teams, Cultivate offers a hyper-personalized and scalable solution to enhance manager effectiveness. Empower your managers to evaluate their effectiveness based on your organization’s leadership competency model or the Perceptyx model using Cultivate 360 Feedback. Additionally, offer AI-powered coaching seamlessly integrated into their daily workflow, leveraging observed behaviors and peer feedback through Cultivate Intelligent Coaching.

-

“In today’s always-on workplace and highly competitive labor market, managers and leaders need advice and support in the flow of work. Cultivate delivers this with impact.”

-

“If Cultivate prevents one person from leaving, it pays for itself.”

-

“Perceptyx helps us gauge performance on our core leadership competencies and the impact of the updates we’re making.”

Support every manager

Extend coaching beyond executives and high performers to drive learning for all managers–at a fraction of the cost–with AI-powered coaching.

Drive a growth culture

Nurture an environment of safe and continuous support to close skill gaps and amplify strengths.

Boost business outcomes

Accelerate performance outcomes like innovation and profitability by reinforcing the leadership best practices that encourage engagement, well-being, psychological safety, and manager trust.

Focus on what matters most

Equip leaders with essential insights into their strengths and areas for development, derived from self-evaluation and input from peers and colleagues they collaborate with.

Cultivate

Cultivate

360 Feedback

Provide the actionable insights managers need to motivate and retain their people today.

- Provide every manager holistic support when, where, and how they need to lead, retain, and coach their team today.

- Generate a pipeline of leaders–and alumni–who possess a true compass to drive the right business outcomes throughout their career.

- Generate a virtuous cycle of leadership development and business success.

Cultivate

Intelligent Coaching

Continuously augment learning with digital signals from platforms like Slack, Teams, Google Workspace, and Office 365.

- Invite managers to opt-in workplace communication insights to inform coaching and maintain privacy.

- Provide personalized guidance based on observable behaviors.

- Empower managers in the flow of work with top-tier resources from Harvard Business Publishing, LinkedIn Learning, or your own LMS.

Customer Stories

With 360 feedback, managers are gaining actionable insights on specific ways to shift their behavior, rather than a general review of their performance.

Learn more about the Principal customer storyPrivate, personalized coaching helped managers gain the trust, agency, and insight to “work and lead the SAP way.”

Learn more about the SAP customer storyWhy choose Perceptyx

Align skills with goals

Empower managers with customized coaching that aligns 360 feedback and either your organization’s leadership competency model or the Perceptyx model.

Expand coaching and improve ROI

Augment human coaching with scalable, continuous, and cost-effective coaching for every manager.

Show the right next step

Continuously guide managers with AI-powered coaching based on their own digital signals from platforms like Slack, Teams, Google Workspace, and Microsoft Office 365 that they opt-in to sharing.

Invest in your leadership pipeline

Demonstrate your commitment to nurturing managers so they can amplify leadership practices across their teams.

Leverage results seamlessly

Give managers, HR business partners, and admins one central Listening Home to manage insights from all listening channels.

Create an engaging culture

Inspire manager confidence and trust through leadership best practices that promote engagement, and motivate their teams to do their best work.

Use Cases

Leadership Development

Nurture managers with the support they need to lead their people through continuous, personalized coaching in their flow of work.

Organizational Performance

Reinforce the leadership practices that drive productivity and profitability through AI coaching and analysis of observed behaviors.

Augment 1:1 Coaching

Increase the impact of existing development programs with intelligent coaching that drives measurable behavior change.

Best Practices

Learn more about Leadership Development

Coaching at Scale: AI Democratizes Leadership Development

What AI-based coaching is, how it augments human-coaching, and why it’s critical for driving overall organizational health

Read more about Coaching at Scale: AI Democratizes Leadership DevelopmentThe Leader’s Guide to AI-enabled Coaching

Examples of AI-based coaching, the nature of digital behaviors, and the impact across organizations with regard to improved relationships, well-being, and leadership

Read more about The Leader’s Guide to AI-enabled Coaching360 Degree Surveys: The Most Important Things To Know

The advantages of 360 degree surveys, the most effective design for surveys, and the most effective ways to use the data generated by 360 degree feedback surveys

Read more about 360 Degree Surveys: The Most Important Things To KnowGetting started is easy

Advance from data to insights to focused action

People Insights Platform

Drive Change, Deliver Impact

Dialogue

Crowdsourced insights to engage your people on the topics that matter most

Learn more about Dialogue productSense

Lifecycle surveys and always-on listening to keep pace with your people

Learn more about Sense productCultivate

360 Feedback and Intelligent Coaching to improve manager effectiveness

Learn more about Cultivate product